Introduction: The Original 3D "Virtual Reality"

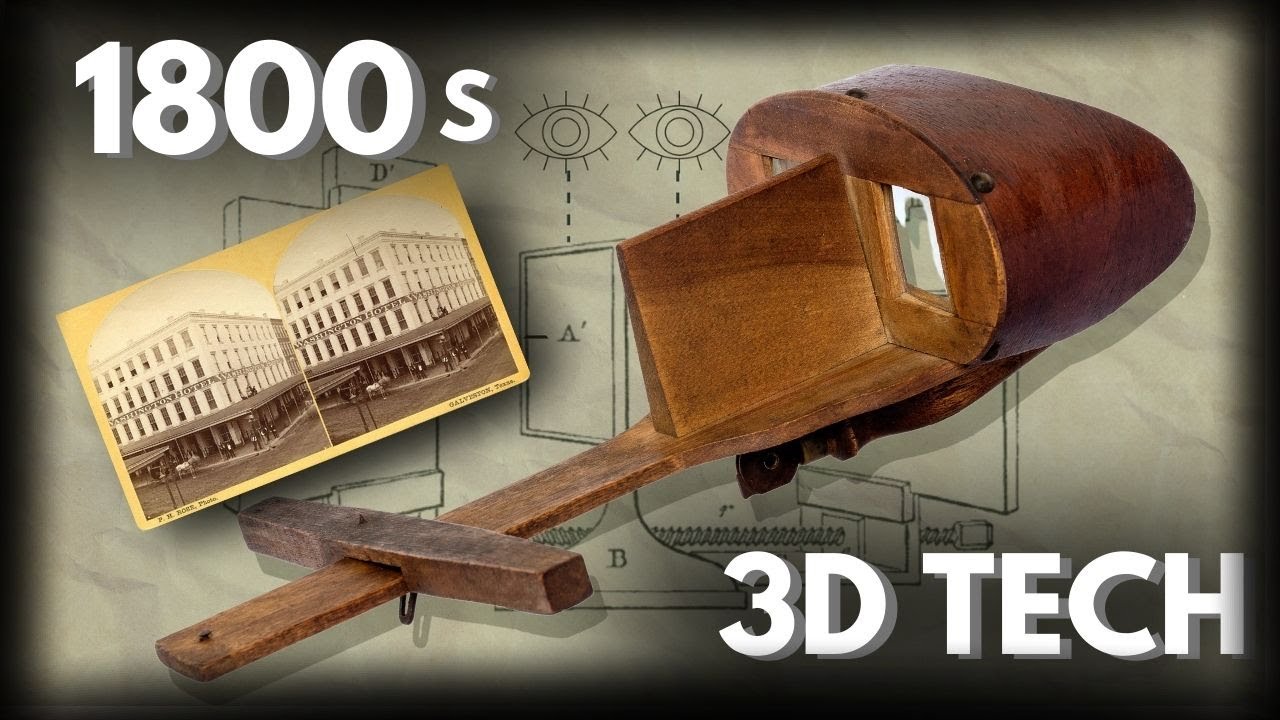

Over the weekend, I came across an 1890s stereoscope viewer and a small stack of stereoview cards at an antique store. It immediately stood out—not just for its age, but because it represents the 19th-century version of 3D viewing, long before VR headsets or television existed.

If you’ve ever used a View-Master or tried a modern VR headset, you’ve experienced the same principle at work. In the late 1800s, stereoscopes were a centerpiece of home entertainment and education. They offered a rare chance to see vivid, realistic images of faraway places and historic events, turning living rooms into immersive viewing parlors.

As someone who owns & shoots stereoscopic cameras from the 1950s, finding this even older viewer was very exciting! It’s a reminder of how groundbreaking stereoscopes were and how they paved the way for the photography and visual technology we take for granted today.

What is a Stereoscope?

A stereoscope is a viewing device that merges two slightly different photographs into one image, creating a three-dimensional effect. Each photograph is taken from a slightly different angle—similar to how our eyes see the world. When viewed through the lenses of a stereoscope, the brain fuses the two images together, producing a lifelike sense of depth (Smithsonian Magazine).

This principle, known as binocular vision, underpins stereoscopic photography (Encyclopedia Britannica). To audiences in the 19th century, who were used to flat prints and engravings, it was astonishing.

Did You Know?

The term “stereoscope” comes from the Greek words stereos (“solid”) and skopein (“to look”), literally meaning “solid view” (Wikipedia). This perfectly describes what it offered—a window into realistic, “solid” images unlike anything people had seen before.

For enthusiasts, the optical design is elegantly simple. Stereoscopes are built to match the average distance between human eyes (about 2.5 inches). Their lenses magnify and align the paired images while subtly shifting angles inward, guiding each eye toward one photo. The slight difference between the two images, called parallax, is what creates the illusion of depth (Watts Gallery).

A Brief History of Stereoscopes

The stereoscope’s story began with science and quickly grew into mass entertainment:

- In 1832, British scientist Sir Charles Wheatstone developed the first stereoscope using mirrors to show two drawings side by side, illustrating how binocular vision works. Photography would be invented just a few years later in 1839, making his concept ripe for photographic application.

- By 1849, Sir David Brewster (Scottish physicist and inventor of the kaleidoscope) replaced Wheatstone’s mirrors with lenses, creating a compact, practical design suited for photographs. His improvements coincided with early photography’s growth, and suddenly, stereoscopes were no longer a scientific curiosity but a household device. The first Brewster-type stereoscopes were made by optician George Lowdon.

- 1861, Oliver Wendell Holmes introduced a simplified, handheld stereoscope. His design was inexpensive, widely adopted, and deliberately left unpatented to encourage mass production

- By the late 1800s, stereoscopes were everywhere. Middle-class families could purchase stereoview cards featuring travel destinations, historical events, or staged domestic scenes. For many, this was their only chance to "see" the pyramids of Egypt or bustling Paris streets.

- In the Early-to-Mid 1900s, stereoscopic viewing evolved with new formats like the View-Master (introduced in 1939) and the Stereo Realist camera (launched in 1947), sparking a revival of hobbyist 3D photography and making stereo imagery popular again among mid-century audiences.

Stereoscopes thrived until the early 20th century, when cinema and illustrated magazines drew public attention elsewhere. By the 1920s, they became more of a collector’s hobby, though they would enjoy a mid-century revival among photography enthusiasts. (See my blog post about 1950’s era stereo cameras: Exploring the Stereo Realist: Vintage 3D Stereoscopic Film For Beginners)

How Does a Stereoscope Work?

Stereoscopes rely on the brain’s ability to combine two images into one 3D scene. A card with two photos is placed in the viewer, each eye looks at one image, and the brain merges them into a single picture with depth (Smithsonian Magazine).

The Viewing Process:

For Victorian audiences, this was transformative. With a simple viewer and a stack of cards, they could “travel” the world from their parlor, experiencing lifelike images that felt immersive decades before moving pictures existed (Watts Gallery).

Types of Stereoscopes

The earliest stereoscopes, invented by Sir Charles Wheatstone in 1832, used mirrors instead of lenses to direct drawings or diagrams into each eye, demonstrating the principle of binocular vision (Watts Gallery). These were large, table-mounted devices and were primarily scientific instruments, predating photography’s invention in 1839. While impractical for home use, they laid the groundwork for all later stereoscope designs.

Popularized in the 1860s, these handheld devices were inexpensive and became household staples (Smithsonian Magazine). These are probably the kind you will find most often at antique stores!

Ornate, furniture-like models often held dozens of cards and were designed for wealthier homes (Antique Photographics).

Enclosed European designs with hoods that blocked out light, creating a more immersive view (Watts Gallery).

Plastic viewers paired with stereo slides became popular in the 1950s, aligning with hobby photography’s boom.

That said, stereoscopes came in various designs that reflected their era and audience.

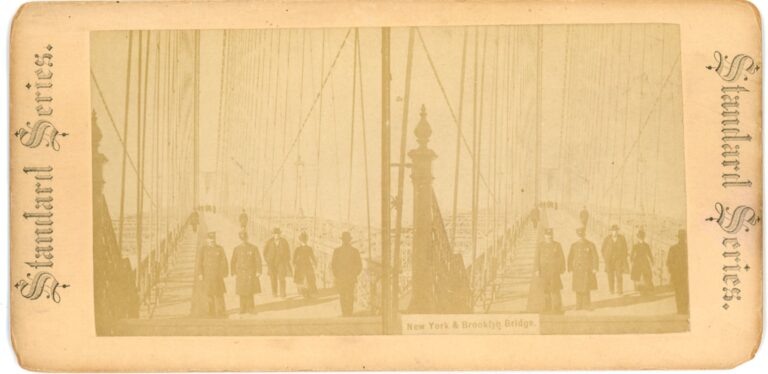

Stereoview Cards: The Victorian Photo Library

Stereoview cards were central to the experience. Each card held two precisely aligned photographs mounted on cardstock. When viewed through a stereoscope, they appeared as a single 3D image (Library of Congress). Cards depicted exotic travel destinations, historic moments, domestic life, and even comedic scenes staged for entertainment. Some were used in classrooms to teach geography and science (Watts Gallery). For many, these cards were their only window into distant lands or major events.

Did You Know?

Tens of millions of stereoview cards were produced worldwide, making them one of the first global photography formats (Watts Gallery).

Today, collectors prize cards featuring rare subjects or pristine condition. Holding one feels like stepping back in time, seeing what fascinated people over a century ago (Stereosite).

Sample Photo Cards

Click the cards below to view:

Value Then & Now: Stereoview Cards & Viewer Prices

Understanding how stereoscopes and cards were priced historically (and what they’re worth today) adds valuable context for enthusiasts and collectors. These devices weren’t just fascinating—they were also priced for mass accessibility.

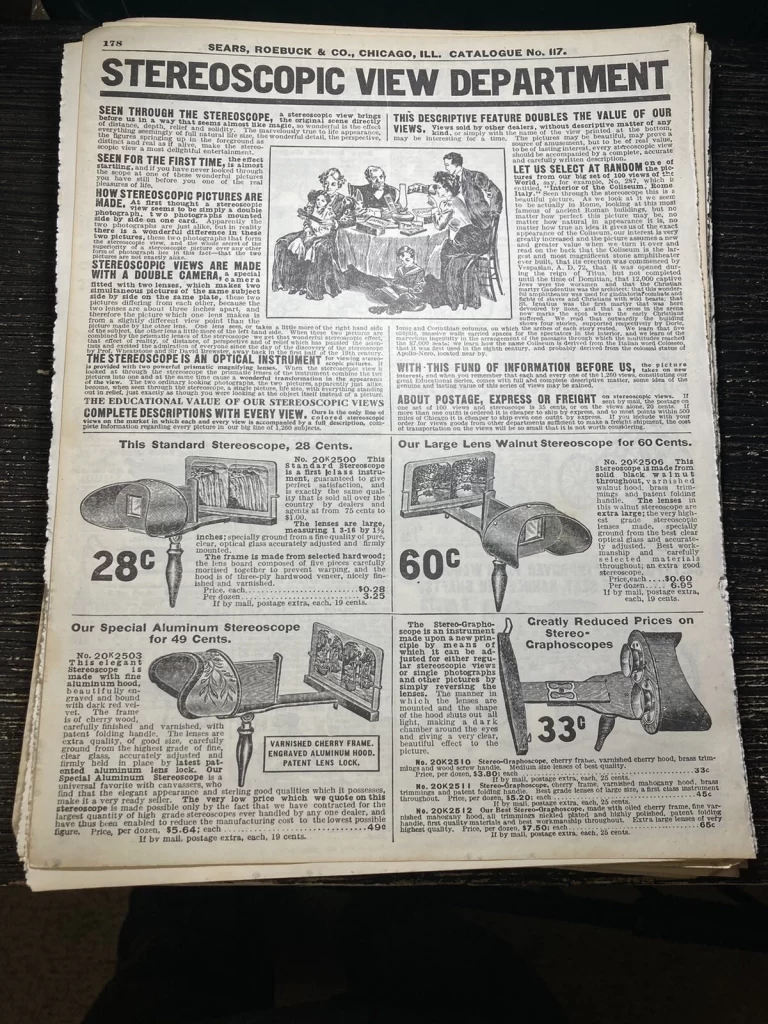

Victorian-Era Costs (Late 1800s)

- Stereoview cards: Typically sold for about 5–15¢ each, making them accessible to middle-class families(Library of Congress). Adjusted for inflation, that’s roughly $2–$4 today.

- Holmes-style viewers: Handheld stereoscopes often cost $1–$2, or about $30–$60 in modern value (Watts Gallery).

- Tabletop or cabinet viewers: More ornate models could cost several dollars (equivalent to $150–$300 today) and were marketed as luxury items (Antique Photographics).

Modern Market Prices for Collectors

- Stereoview cards: Common scenes sell for $3–$15, while rarer images (e.g., such as disaster scenes, historical events, or pristine condition images) can sell for $50–$300+ especially if they come from major publishers like Underwood & Underwood.

- Handheld Holmes viewers: typically range from $50–$200, with sets including cards often selling for $100–$250 (eBay Canada).

- Tabletop/cabinet viewers: high-end models can sell for $500–$1,000+, and exceptional or rare examples may reach $2,000+ (Stereosite).

Looking for more information on collecting stereoviews? Look for Auction sites, or check online retailers like Ebay. This article from Britannic Auctions is incredibly insightful: Seeing Double: An In-Depth Guide to Stereoviews, Their Collectibility and History

The Consumer Experience

In the late 1800s, stereoscopes were as common in parlors as bookshelves or pianos. Families gathered around to browse cards, share stories, and “travel” visually without leaving home (Smithsonian Magazine). They were affordable, sold through mail-order catalogs or door-to-door, and widely promoted as both educational and entertaining. Schools and libraries also used them as teaching tools (Library of Congress). This mix of novelty, accessibility, and social enjoyment made stereoscopes one of the most popular visual media formats of their time.

The Photographer’s Side

Behind every stereoview was a photographer skilled at creating depth. Professionals like Thomas Richard Williams and Charles Bierstadt produced iconic images published by companies such as Underwood & Underwood and Keystone View (Wikipedia).

By the 1950s, stereo photography shifted toward enthusiasts. Cameras like the Stereo Realist allowed hobbyists to easily capture paired images on 35mm film, while figures such as actor Harold Lloyd documented Hollywood and everyday life in 3D (Medium).

This blend of professional craftsmanship and hobbyist creativity helped stereoscopic photography endure long after its initial boom.

Modern Collecting & Relevance

Today, stereoscopes and cards attract both collectors and photography enthusiasts. Handheld Holmes viewers are common finds, while ornate cabinet viewers or rare stereoviews featuring historic events fetch higher values (Stereosite).

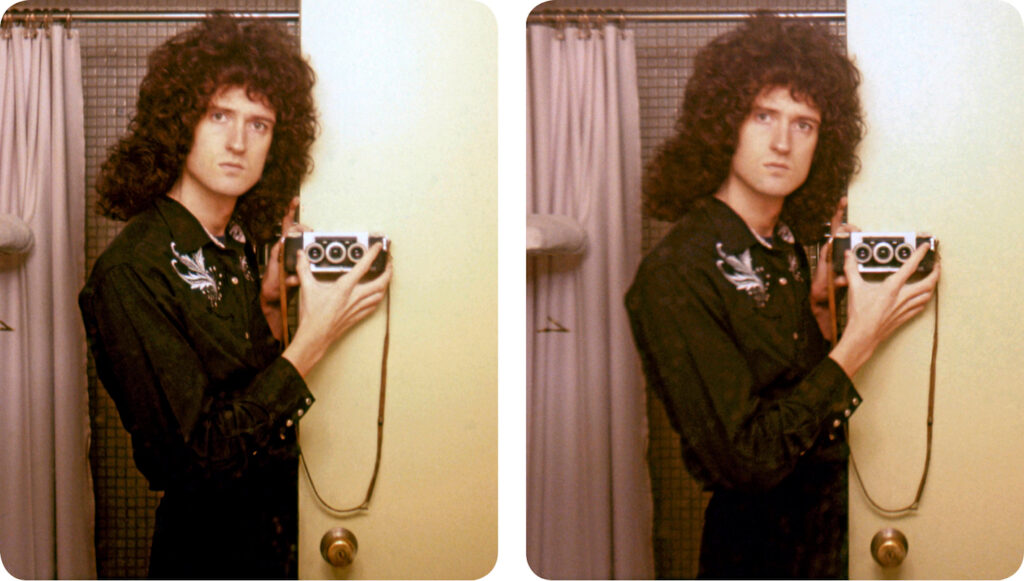

Interest has also been revived by figures like Brian May of Queen, who re-established the London Stereoscopic Company to reprint historic stereoviews and keep the tradition alive (Smithsonian Magazine). He even published his own book called “Queen in 3D” with over 300 photos mostly taken by Brian himself. Check it out on Amazon!

Below is one of my personal favorite photos from the book. If he ever happens to stumble across this blog post, I hope my choice gives him a good laugh because it’s pretty iconic, haha.

Fun & Helpful Videos

Stereoscopes

5:34

1:17

Conclusion

Stereoscopes were more than novelties, they were photography’s first immersive medium. They combined science, entertainment, and education in a way that brought the world into people’s homes long before film or television.

Discovering an 1890s viewer reminded me how innovative they truly were. If you see one in an antique shop or museum, take a look. You’ll experience the same wonder that captivated viewers over a century ago, and see just how far photography has come.

Warm regards,

Lexi

Resources & Further Reading

If you’re interested in learning more about stereoscopes, stereoview cards, or stereoscopic photography, here are some excellent resources I recommend:

- Stereoscope on Wikipedia — A general overview of stereoscopes and their development.

- Smithsonian Magazine: Stereographs, the Original Virtual Reality — A fascinating deep dive into their cultural impact.

- Library of Congress: Stereograph Card Collection — A rich archive of historic stereoviews and educational use.

- Encyclopedia Britannica: Development of Stereoscopic Photography — Contextual history of stereoscopic photography in the larger photography timeline.

- Watts Gallery: A Short History of Stereoscopy — Great resource on the Victorian-era fascination with stereoscopes.

- Antique Photographics: Stereoscopes & Stereoviewers — Insights into collecting and understanding different viewer styles.

- Stereosite: Collecting Stereoscopes — Tips on identifying, valuing, and collecting antique stereoscopes.

- Stereographer: Appraising Stereoviews — Detailed guide to pricing and valuation for collectors.

- London Stereoscopic Company (Brian May’s Revival) — Modern revival of stereoscopic photography and reissued stereoviews.

- Britannic Auctions – Seeing Double: An In-Depth Guide to Stereoviews, Their Collectibility and History

Previous Post

Top Search Trends About AI in 2025: What People Actually Want to Know, According to Google