TL;DR

I found a November 1960 issue of Life magazine featuring an article on Martin Luther King Jr., written while the Civil Rights Movement was still unfolding. Reading it now—after growing up learning about MLK through textbooks and commemorations—offers a rare, first-hand look at him not as a finished historical figure, but as a leader navigating uncertainty in real time. This piece reflects on that article, the moment it captures, and why physical archives like this still matter today.

Finding the Article

I came across the November 7, 1960 issue of Life magazine at an antique store, mixed in with other mid-century issues focused on space, science, and global discovery. The cover headline, New Portrait of Our Planet & What IGY Taught Us, felt very of its time, optimistic and outward-looking. The article on Martin Luther King Jr. wasn’t the feature draw, but something you encountered as you moved through the magazine, alongside advertisements and photo essays that reflected everyday American life in 1960.

Reading it just after Martin Luther King Jr. Day made the timing feel intentional, even though it wasn’t. This wasn’t a piece written to explain his legacy or smooth the edges of his work. It was contemporary reporting, written while events were still unfolding. King appears here without the benefit of hindsight — presented as a leader navigating real consequences and public scrutiny, not a figure already secured in history. That framing is easy to forget when his life is more often encountered through speeches, monuments, and anniversaries.

Read the Full Article:

Read the full article below:

Want to see the full magazine?

I’m currently digitizing the magazines in my personal collection, including this issue of Life. You can explore the archive as it grows in my Vintage Newspapers & Magazines collection.

Where MLK Jr Was in 1960

By 1960, Martin Luther King Jr. was already a national figure, but the Civil Rights Movement itself was still unsettled. The Montgomery Bus Boycott (1955–1956) had proven that nonviolent protest could work, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference had been established in 1957, but there was no clear blueprint for what came next. King was visible, often targeted, and increasingly expected to respond to events as they unfolded rather than lead from a distance.

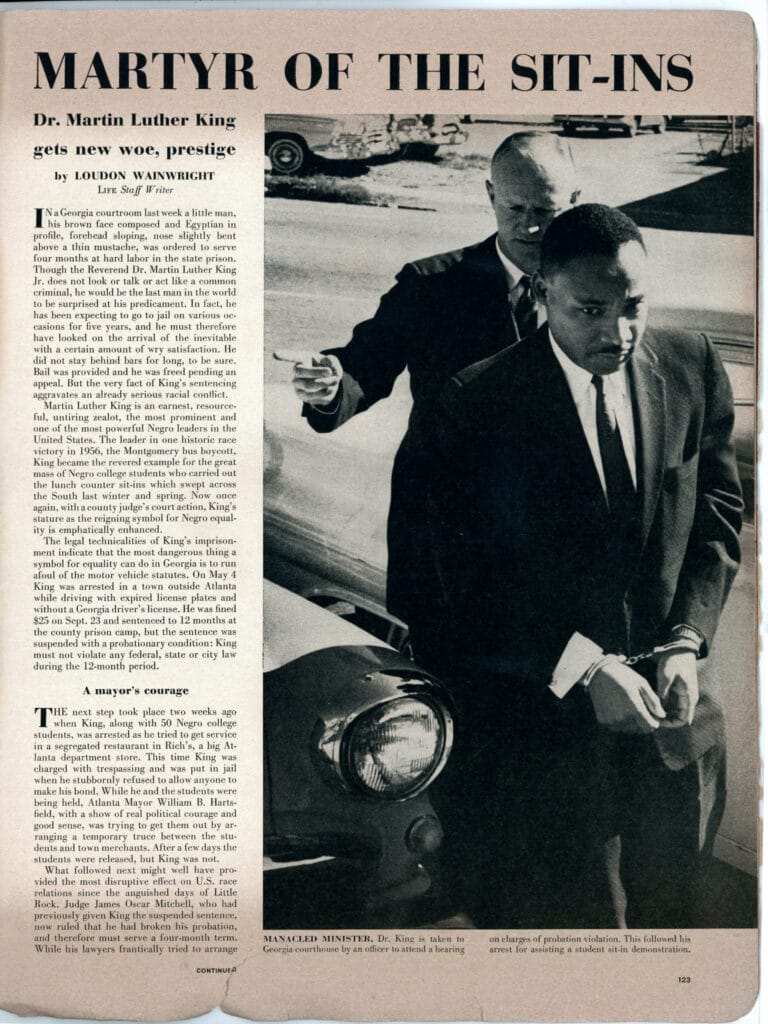

This moment sits between milestones that are easier to recognize in hindsight. It comes before Birmingham (1963), before the March on Washington (1963), before the Nobel Peace Prize (1964). In 1960, King’s role was still being analyzed and negotiated… by the media, by politicians, by local organizers, and by King himself. The article above reflects that instability. It captures a leader whose authority was constantly tested by arrests, public scrutiny, and the real-world effects of nonviolent resistance in a segregated South.

The Sit-Ins and a Movement in Transition

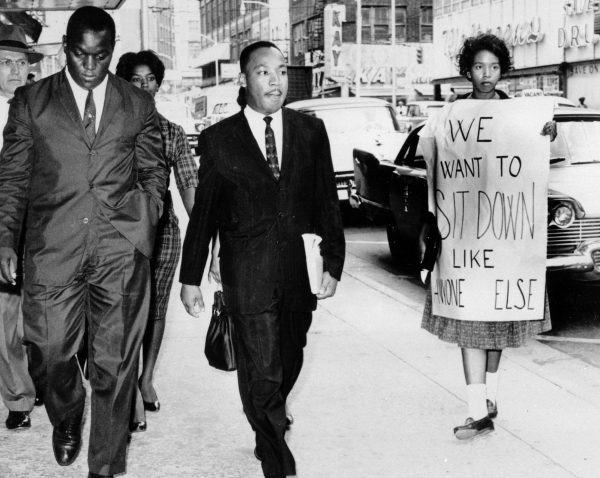

Image Source: https://www.history.com/articles/the-greensboro-sit-in

The sit-ins that began earlier in 1960 changed the scale and texture of the Civil Rights Movement almost overnight. What started with a small group of students refusing to leave segregated lunch counters quickly spread to cities across the South. These were local actions, often loosely organized, and led by people who were not waiting for permission or national leadership to act.

At this point in the Movement, King appears less as the origin point and more as someone responding to momentum already in motion—supporting the students, reinforcing nonviolence, and helping connect their actions to a broader strategy. The movement was becoming younger, more diffuse, and harder to control, and that change brought both possibility and risk. In 1960, it wasn’t yet clear how this energy would sustain itself, or what it would ultimately demand from those already at the center of the struggle.

How Life Magazine Portrays MLK

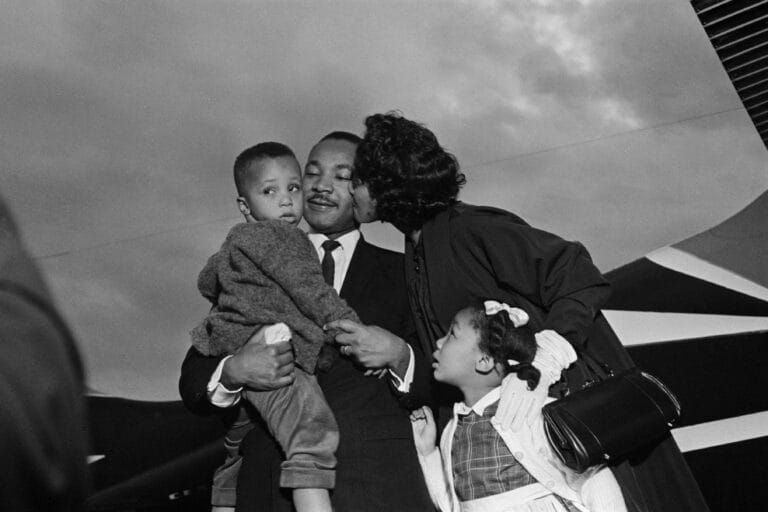

What stands out most to me in this Life magazine article (reading in retrospect, of course) is how unfinished Martin Luther King Jr. feels. As we see in the author’s language and tone, he isn’t yet presented as one of the greatest nonviolent leaders in American history, but as a man actively navigating pressure from the courts, from the public, and from within the movement itself. The article lingers on his arrests, his strategic thinking around nonviolence, and the constant balancing act between leadership and exhaustion. Alongside this, there are glimpses of domestic life and quiet moments that feel almost fragile when placed next to images of confrontation and authority. Reading it now, it’s striking how little certainty the author assumes about outcomes. There is no sense of inevitability, no promise that the movement will succeed, only the documentation of a leader working through risk in real time. In this way, Life captures King not as history, but as a presence: active, contested, and still becoming.

Why This Article Hits Differently Today

King’s work is presented as necessary, but also risky, exhausting, and unresolved. The movement itself feels fragile — dependent on individual choices, public response, and the willingness of people to keep showing up.

As most of us did, I grew up learning about Martin Luther King Jr. through textbooks and classroom timelines, where his life is often presented in completed arcs and defining moments. Encountering him here, in a piece written while events were still unfolding, feels fundamentally different. There’s an immediacy to it that doesn’t exist in retrospective accounts, and for someone who has always been drawn to history, there’s something genuinely exciting about reading a first-hand account rather than a posthumous interpretation.

This article sits before the language of legacy takes over. It shows a version of King whose future isn’t settled and whose significance hasn’t yet been agreed upon. Reading it this way makes the distance between lived experience and historical memory more palpable… and harder to ignore.

Why Physical Archives Matter

Reading this article in its original form adds context that’s easy to lose in fine-tuned excerpts or summaries you find in textbooks. It sits among advertisements, global news, and photo essays that reflect what everyday life looked like in 1960, not just what history later decided was important. The Civil Rights Movement appears here as one part of a much larger world, not the only story being told.

That proximity matters. It’s a reminder that these events didn’t unfold in isolation, and that progress existed alongside indifference, optimism, and distraction. Holding the magazine makes that coexistence harder to ignore.

There’s also something materially different about encountering journalism in print. Once published, this article couldn’t be quietly revised, reworded, or removed without leaving a trace. In contrast, digital journalism today exists in a constant state of revision — headlines change, articles are updated, context shifts, and older versions often disappear unless they’ve been deliberately preserved. Archivists and journalists have long debated what this means for public memory: printed media fixes a moment in time, while digital media prioritizes speed, reach, and adaptability, sometimes at the cost of permanence.

Reading this magazine now underscores that difference. The article remains exactly as it was written in 1960, complete with its framing, limitations, and assumptions. It hasn’t been optimized, corrected, or softened by decades of reinterpretation. That immutability doesn’t necessarily make it more accurate, but it does make it accountable. It shows how history was recorded when it was still happening, and why preserving those original records still matters.

Closing

This article doesn’t offer a complete story, and it isn’t trying to. King appears here not as a fixed reference point, but as someone moving through uncertainty, making decisions without guarantees.

Reading it now makes it harder not to think about the present—about how many things unfolding around us will later be described as turning points, even if they don’t feel like that yet. Most moments that end up mattering most don’t announce themselves so plainly. They sit within everyday life, documented imperfectly, surrounded by distractions, waiting for time to give them shape.

Revisiting pieces like this is a reminder that history isn’t experienced as history while it’s happening. It’s lived in fragments, often without clarity, and rarely with consensus. Holding onto those fragments before they’re smoothed into something more clear-cut or digestible may be one of the most honest ways to remember.

Image Source: https://gwtoday.gwu.edu/man-all-seasons